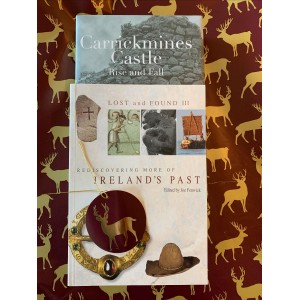

TWO GREAT BOOKS ONE GREAT PRICE!

LOST & FOUND 3

The number three has a pleasing symmetry. This is the third volume in the Lost and found series, and the concluding one. It has come full circle. Indeed, one of the essays in the first book, which provided the eponymous title of the series, was to lead to an interesting discovery in its own right, the curious tale of which concludes this final volume. It is also interesting to note that Professor Etienne Rynne, in his Foreword to Vol. 2, requested that he write the first essay in the next volume, having written the concluding essay in the first. Sadly, he was lost to the archaeological world in the summer of 2012 before he could fulfil his wish, but his indomitable spirit can be found in the opening essay of this volume, as is entirely appropriate. These two essays, therefore, neatly book-end this third volume and seem to suggest that this is the proper place to conclude the series—and so it does.

The first rule of this volume, the authors were informed, is that there are no rules. Each was simply asked to write on the subject of ‘discovery’, however they chose to define it. They were asked to adopt an easily accessible style and avoid the constraints of academic convention (the formal language, the obscure jargon and the over-zealous use of citation and footnote) though a brief bibliography of further reading was encouraged. In order to point people in the right direction, a brief ‘style-sheet’ was produced, which (of course) was roundly ignored by everyone who took the first rule to heart. Based on the previous experience of Vols 1 and 2, I had expected variety, novelty and creativity, but I had not anticipated the total anarchy in terms of content, style and format that was to come my way for the third. I wrestled valiantly with the first few essays in a vain attempt to enforce the ‘style-sheet’, pleading with authors to see sense, but I was simply overwhelmed by successive waves of uncompromising obstinacy and an almost universal tendency to adopt a ‘freestyle’ format until a point was reached where I had to concede defeat. I was both outnumbered and outgunned. It was far better, as I was soon to discover, to relax, ‘go with the flow’ and trust the individual author’s instincts. And who was I, as a humble field archaeologist, to argue? Each essay, after all, is written by an eminent scholar or recognised expert in his or her own field. The content can be trusted to be genuine, well informed and factual. I’ll confess, however, that the format and style of the book diverges somewhat from the norm, but I am all the more grateful to everyone for that. The result is a wonderfully unruly anthology of essays, a wildly exhilarating theme-park of novelty and wonder. It is a book for the fearless, thrill-seeking reader—a rollercoaster ride through the fairgrounds of archaeology, Celtic studies, Classical studies, geology, geophysics, history, Irish studies, musicology and more.

The Walshes were rooted in south County Dublin from the late fourteenth century. By the early 1600s members of the family had become actors in the theatre of war across Europe. These were times of almost endless turmoil. A constant stream of predicaments affected the lives of kings and queens, bishops and lords, men and women across the Continent.

CARRICKMINES CASTLE

Theobald Walsh of Carrickmines had not intended to defend his castle. The commander of the besieging forces, Sir Simon Harcourt, had not planned to attack it. Yet in March 1642 the castle was destroyed and hundreds of its occupants massacred. How did this come to pass?

Carrickmines had a simple beginning as an isolated habitation in a relatively fertile river valley. Once the settlement found itself on an emerging frontier in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, its character, and the lifestyle of its occupants, fundamentally changed.

Over five centuries Carrickmines would evolve from an open settlement to a defended farmstead, a fortified border outpost and a wealthy manorial centre. The Walsh family were established by the late fourteenth century. Their holdings would expand to Shanganagh, Kilgobbin and Balally in south County Dublin, and Old Court and Killincarrig in County Wicklow.

In the early seventeenth century Theobald Walsh, his father and other relatives soldiered on the Continent. The Walshes, like many other families from Ireland, were drawn by the opportunities available in the service of the Habsburg Empire. It was their misfortune that the wars would arrive at their own door. Sir Simon Harcourt, the besieger, was a veteran of the wars in Germany, Holland and Scotland, serving in the armies of both England and the embryonic Dutch state. His wife and confidante, Lady Anne, awaited his return in Oxfordshire. After two eventful days in March 1642, however, nothing would ever be the same again.

| Details | |

| Author | Edited by Joe Fenwick |

| Publication Data | 2003 |

| Subjects | General Interest |

ARCHAEOLOGY DUO

- ISBN: ISBN9781869857684

- Author(s): Edited by Joe Fenwick

- Availability: In Stock

-

€45.00